07 August 2020

by Rey Armenteros

This is a response to an article at The Comics Journal (abbreviated as TCJ), published by Fantagraphics Books. The article attempts to belittle a rival publisher (Yoe Books) of classic comics reprints, and it is followed by a long list of scathing comments, most of them against the targeted publisher. Note that R. C. Harvey, who does defend Yoe Books and is mentioned in my comment, is not to be confused with the article’s writer (since their names have a similar construction). The article can be found here:

TCJ Article on Yoe Books

And here is my response:

I am nobody but a fan, and I don’t have as much ideological insight into the ethics behind making reprints of old comic art, but there are a number of things that make a response to this webpage impossible to avoid. Here are the facts as I see them through my personal experience with such books.

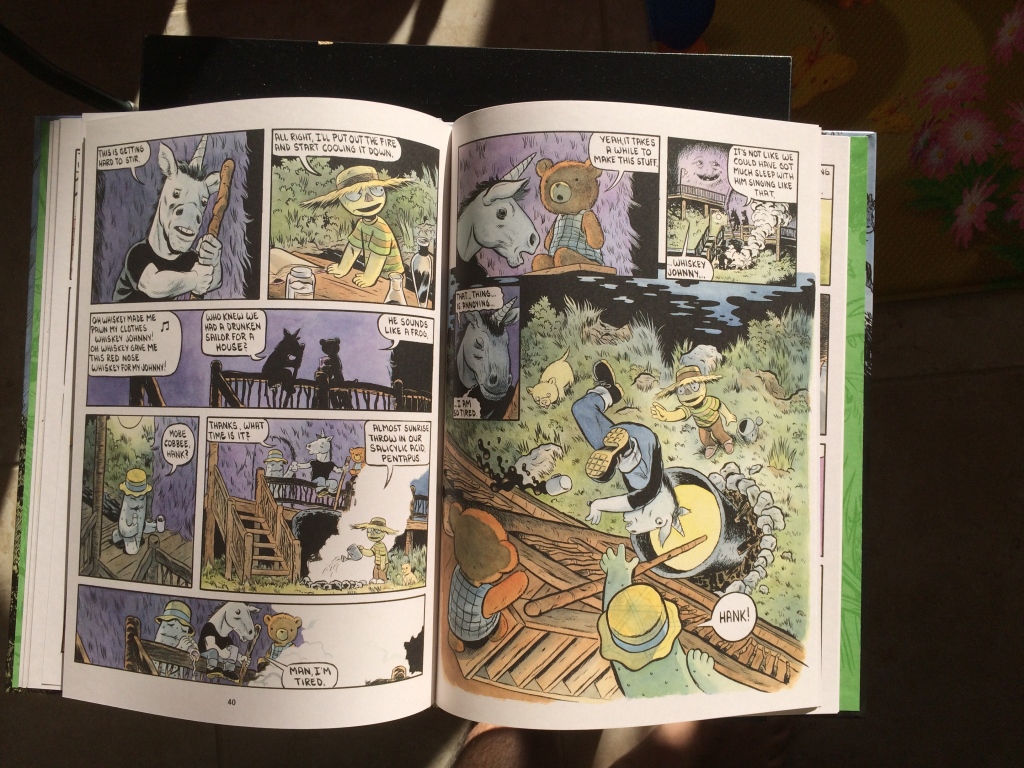

I own about twenty Yoe Books that reprint old comic work. As far as production values — quality of paper and other materials, the strength of the binding, the richness of the ink — they are stellar. The printing plates themselves are crisp, so much so that you can read the dots and lines of the color screens without the blur you used to see in older reprints.

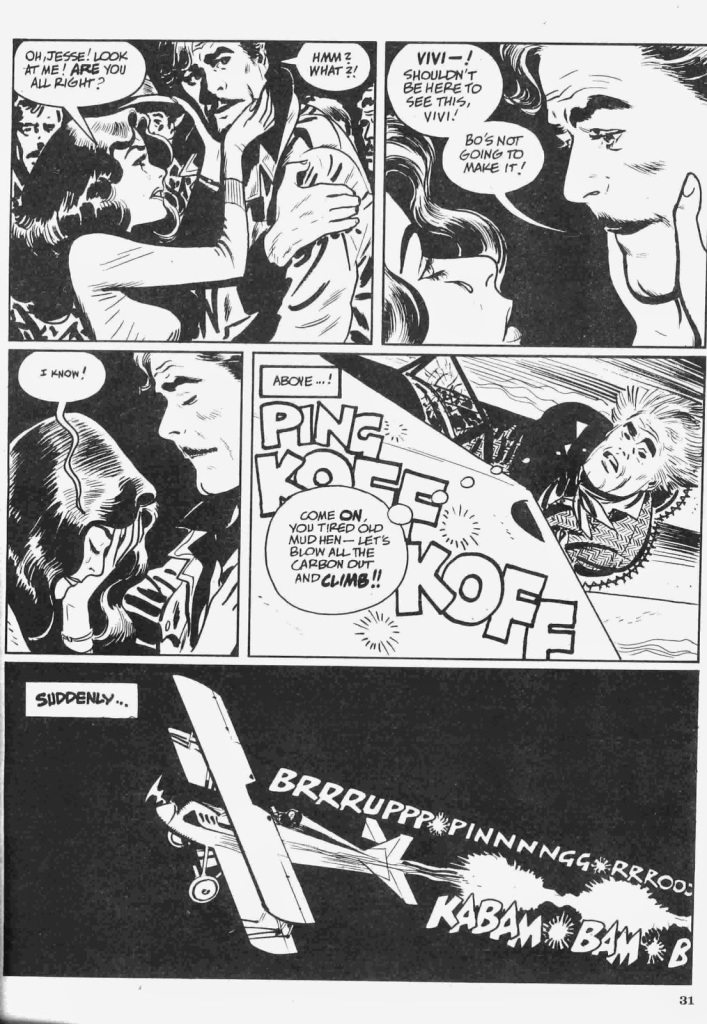

After reading the article and the comments, I wondered where all this anger came from. The real culprit in this exchange comes from the question of esthetics. And this could be largely based on opinion. This philosophical debate has no real answers because all conclusions stemming from them will only come from preference. There are those publishing companies that ruin old art by recoloring it according to today’s standards using imaging programs that jazz up the art, and there are people out there who actually enjoy this mistreatment of the old material. Other publishers retain an approximation of the flat coloring but ramp up the intensity, giving us candy-colored versions of the originals, usually on slick papers that feel nothing like the comics of yesterday.

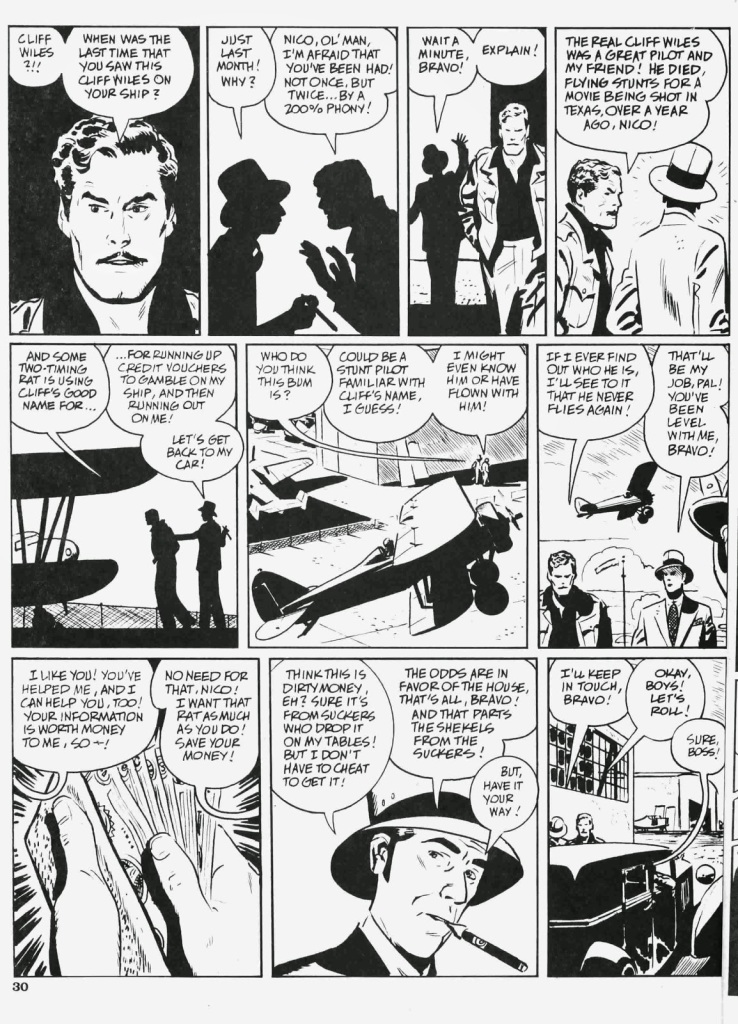

To my mind, the only companies that are doing it right are the ones that come closest to the old colors, and from this, I have found two divergent printing philosophies. There is the one honored by companies like Fantagraphics and IDW, where they come as close to the material without allowing for the blemishes of the slipshod printing of the day. They take the time to clean up the materials in order to give an ideal of what the original publisher might have been going for if precise coloring were possible. And I do appreciate the effects of this approach because it gives us an ideal that never really existed before.

The other one comes from the concept that you shouldn’t have to do this because one of the aspects that we might have enjoyed from those old comics was the imperfect execution of the coloring from the press. I am satisfied when reading book reprints from either approach, but I actually prefer the apparent hands off approach of Yoe Books, and I am going to tell you why.

As a painter who works in a contemporary vein, I can appreciate the beauty that comes from the meeting point of artistic intentions and blind accident. It creates some interesting effects. When I first encountered Yoe Books with the Chilling Archives series, I found pages whose color objectives had been dismantled by age or shoddy printing practices — and I found gold! Many of these pages created optical mixtures of broken colors you might find in a painting by Van Gogh or Monet. On art with such thick paint, dots and dashes of red and blue create purple that mixes in the eye rather than on the palette, without losing the blue and red. Such mixtures have a tendency to move and shimmer. They are by their nature attractive.

Such color mixtures already happen in the traditional CMYK printing of comics because of the coarse nature of the dot patterns in classic comics, but when it is too perfectly aligned, it feels mechanical, and that shimmer is just not there. If unpredictable blemishes and inconsistencies appear, it absolutely scintillates.

This visual delight is exactly what Yoe Books accomplishes. I believe Yoe’s methods appear to be straightforward but they are not simple, since he keeps the original screen patterns in the colors without getting moire patterns or other unwanted printing artifacts. Looking carefully at some of the pages, I find evidence of slight color correction to get harmonious effects that would have been lost if printing the pure scan. Craig Yoe is an artist in his own right. It is evident Yoe takes the time to capture these esthetics; he’s not just grinding these books out.

Which takes me back to this argument being a question of esthetics. It is based on opinion. I love these imperfections, but I understand that not everyone would necessarily appreciate them. The argument should have been centered on this dynamic, not on whether Craig Yoe’s reprint ideals are correct or not, or if “comics history is worse off” for his efforts, which is the conclusion the article posits in the end.

Few of the commenters defend Yoe, and the ones that do don’t really go into the more appealing aspects of his decisions. They just mention things like fun and the old days, and they fail to be very convincing. The only one that does is R. C. Harvey, who places a few good points about Yoe’s scholarship, and who is then subsequently attacked by another commentator, who claims Harvey accuses the writer of this article of attacking Yoe and then resorts to saying Harvey is attacking the writer himself. In fact, the word “attack” is used quite a bit on this webpage, and I don’t think it is out of order. The entire thing is nothing less than bald-faced attack against a publisher who has done nothing to merit such reactions.

When facing an article like this, you have to ask yourself why the producers of the article would agree to publish such charges against a fellow publisher? The immediate thought is that it stems from some form of competitive malice. I don’t think this is the case, but the feeling can’t be shrugged off; it is a precarious position for a publisher to place themselves in. This type of journalism degenerates to mud slinging, and I don’t think that is what TCJ readers came here for in the first place.

Let us take a look at some more facts. I own about fifty reprint books by Fantagraphics. And on the subject of production values, here are some things I found. I bought Roy Crane’s Hurricane Isle put out by Fantagraphics, and it had pages upon pages where the ink was thinned — just gray. I returned it to get another copy, thinking it was a fluke. The replacement had the same problem and in addition, had a flimsy binding. Upon closer inspection, the first copy had a flimsy binding too, and the one I ended up keeping is in worse condition today.

Four Color Fear is a beautiful book, but the cover recently came off completely! I had to repair it with some acrylic medium. Since I baby my books, there was no external reason why the glue simply stopped working. I don’t keep my favorite books in a heated garage, and even those books I have kept in heated conditions do not have this problem.

The L. B. Cole book was sturdy — at first. I have barely looked through the book, and now, the flexicover, which looks like it was stitched, is also coming off the rest of the book, and the reason is because it is actually glued, and once again, the glue has lost its tack.

I have over a dozen of the softcover Krazy Kats that Fantagraphics had put out in recent years. In much of the black and white pages, the art looks like it came off of mediocre photocopies. I understand that this may be because the only source material is the aged newspaper comics pages, and George Herriman’s crosshatching is incredibly difficult to clean up. But since the subject of disrespecting creators with questionable production values had been raised by the article’s writer, I just had to mention this one against one of the medium’s greatest talents.

From where I am looking at this, it is irony incarnate that Fantagraphics would agree to publish this article, when for me, it is doing nothing but pointing the finger right back at Fantagraphics. I never made a big deal about the problems in some of their printing until the day they green-lighted an assault on a fellow publisher who is, by contrast, consistently doing it right.

Understand that I do love Fantagraphics, and I believe TCJ has always been a comics journalism hallmark. I know they are not infallible, but they are certainly above putting out this type of material.

I know not a thing about this RJ Casey. But I do know that this piece of writing under his name is spiteful. And in another bit of irony, the integrity of this article begs the question if TCJ is better off without such “journalism,” and I’ll let you fill in the blank.

Leave a comment |

Categories: Argument, Comics, Essay, ReyA'

|

Tags: argument, comicbooks, comicsjournal, essay