Dynamic Light and Shade

Burne Hogarth’s series of art instruction books continues with this volume that centers on shading. It is over150 pages populated by many black and white illustrations and minimal text. Most of the drawings are by Hogarth himself. Is it a worthy art instruction book?

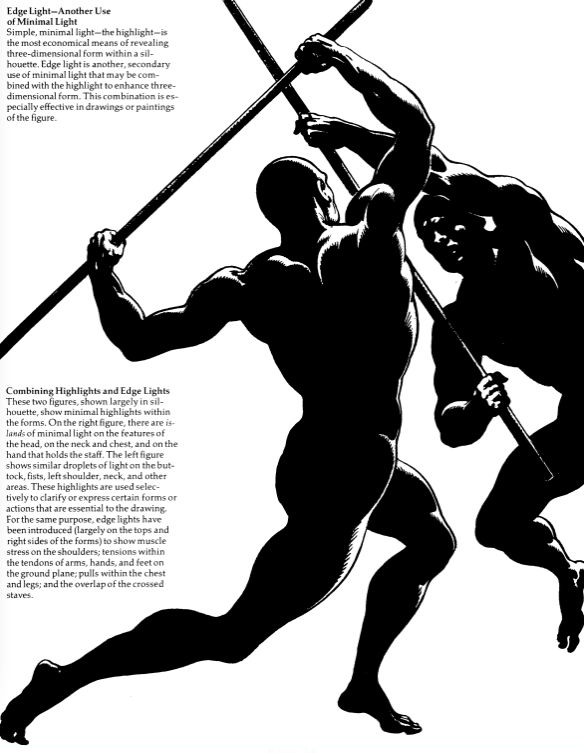

Hogarth begins with the idea of silhouettes and how even in their flat and limited capacity, you can imply spaces and relationships between objects. He follows that chapter with edge light, which is when you take a silhouette and penetrate its flatness with hints of highlights around the edges of forms.

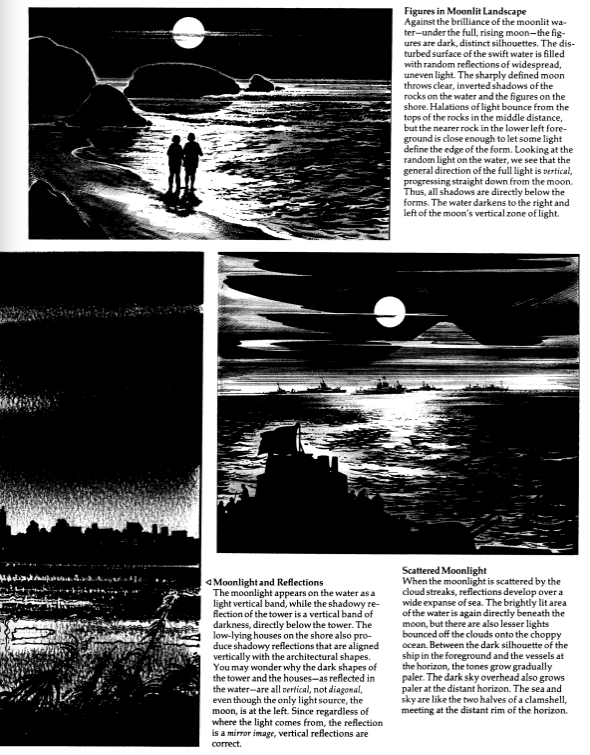

In the third chapter, he delineates the nature of light and shadow in five types of general situations. The first one follows when an object is hit by a single light source. Then, he brings up the characteristics of dual light sources (one strong, direct light source and an indirect light source on the other side of the object). Next, he goes into diffused lighting, which is when the light sources are not distinct, such as during an overcast day. He has a category on nothing more than moonlight. And the last one is sculptural light, which is not a lighting situation that happens in nature but more of an art technique where you shade forms in order to heighten the form rather than to form realistic lighting.

He continues with other lighting situations that each get a chapter. Similar to the idea of sculptural light, spatial light and expressive light are less about depicting a natural occurrence and more about using light to manipulate the viewer’s focus or raise some higher emotion, respectively. Environmental light are the weather and seasonal conditions that can come into play, and textural light focuses on the surface texture of objects. Transparent light illustrates a few strategies when drawing objects that have transparency. Fragmentation light underscores those situations wherein light breaks up, such as light on choppy waters. And radiant light is light that is in some way aimed at the viewer.

When I teach shading, I go about it differently, but I find some sense in his categories. At first, I was reluctant to accept a distinction for the very specific moonlight, but as I read what he had to say about it, I felt that he was presenting a situation that conflated two other categories, the single light source (the moon) with a diffused light (since the moon is not a direct light source but a reflective one that can render dim contrast).

Each category is detailed in a chapter, and each chapter gives variations for the student to understand some of the possibilities within each category. One of the biggest problems with the book is that there is no formal text. Each chapter starts with a paragraph and the rest of the words are confined to captions. In other words, he is doing very little instruction but providing many examples. He never goes into explaining how one might go about doing this, and I suppose for a beginner, it would be frustrating. Actually, I would not recommend this to anyone who is closer to the side of novice drawer; this is better put to use with someone who already knows some things about shading.

As a textbook, it could have some use, since the instructor could fill in for all the gaps in the book. It could be used as a sampler of things to look for. You could even use it to copy (as an exercise) Hogarth’s drawings. Nevertheless, it is so steeped in his comic book style, that anyone not interested in such heroic drawing will not get a lot of value from it.

Curiously, it works best as an art book that showcases the art of Burne Hogarth. His stylized drawings are reminiscent of his work on the Tarzan newspaper strip, but they are rich with intricacies that make you want to keep the book for that value alone.