21 February 2021

by Rey Armenteros

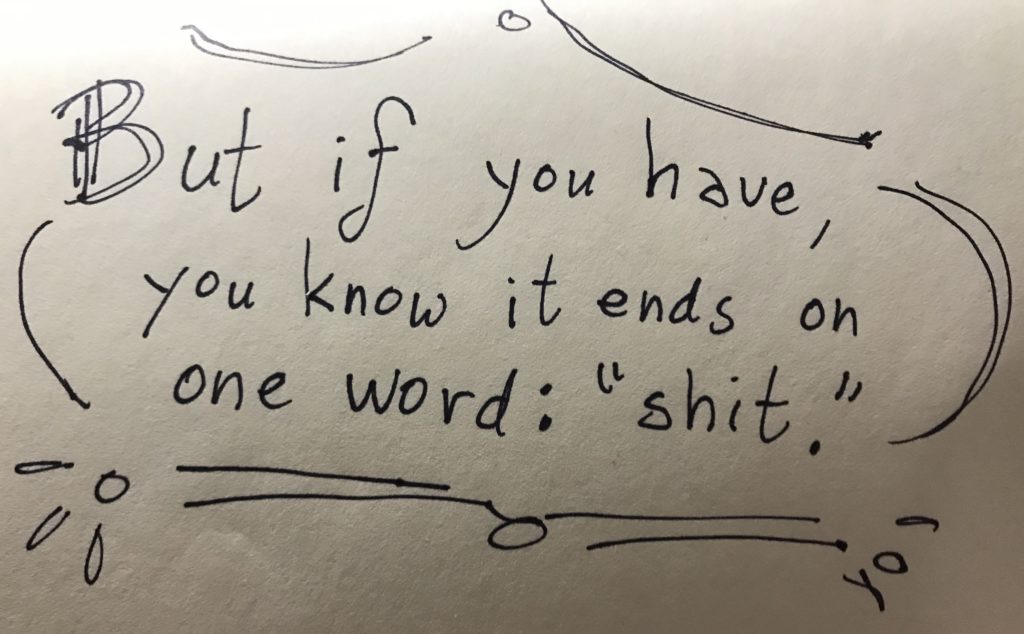

It is likely you’ve never seen my essay titled “The Notebook.” It was published in the literary journal, The Nasiona. But if you have, you know it ends on one word: “shit.”

That one word was called into question by another literary journal. I was having the essay make the submission rounds. This is before the Nasiona had accepted it. I got a number of rejections.

Rejections from literary journals are almost never personalized. They usually start out with how honored they are about my interest in their journal. Then, they mention all the great work that had arrived and about how much they appreciate this too. At about this point, the general rejection letter uses the word “however” and they say something to the effect that they can’t publish everything. More often than not, they use the word “unfortunately” for this task and then mention they can’t publish your work. They finish off the rejection letter with “Good luck” or “Much luck in your endeavors.”

They never call it a rejection. They no longer reject. The new word is “decline.”

When you receive enough of these, you find you are no longer paying attention to the words that show up a lot. If you say “unfortunately” enough times to yourself, you might find the word no longer means anything after about two minutes of this.

However, once in a while, the declination you receive does not mince words like that. Unfortunately, they found that your work “does not fit our journal at this moment,” and they don’t apologize or wish you any kind of luck. And then you find yourself missing those two or three keywords that you thought didn’t mean anything to you anymore since it was those words that kept getting used for things that were called declinations but were actually rejections.

Nevertheless, I am not here to talk about any of those words today. I am here to talk about the last word in my essay, “The Notebook,” which was the word, “shit.” This word was called into question when the essay was declined by a certain literary journal. In this day and age, this literary journal committed the generous act of actually sending me a declination letter that was personalized. Though no one wants a rejection letter (by any other name), any reasonable writer has to appreciate when a publication reaches out and actually gives you feedback. This particular letter sent me feedback on the pros and cons of my essay and why they chose not to publish it.

A personalized rejection was a rare thing, like a fifty-dollar bill rolling around on the sidewalk with no one around to witness you picking it up. It is a gift, in other words, but I was starting to scrutinize this gift because not only was it not what I wanted — it must have been given to the wrong person.

It was the personalized comments themselves that gave me a moment of pause. It made me want to write back. I know my reaction is not normal, but I went ahead and did it anyway, because as I was putting it in my response to their letter of declination, they “opened the dialogue by granting me these observations, and I needed to take this opportunity to retort.”

My letter continued by stating that of the four negative points they found with the essay, two of them were purely subjective, and I had no contention with them.

But on second thought, I did. One of the subjective arguments brought up the idea that the comments about art I made really didn’t go anywhere in the essay. And my response was that they were never meant to go anywhere. They were only there to serve as a comparison with the things that were being said by the stranger I had met as narrated in the essay. That was it.

The other observation that I am categorizing as subjective stated that though they enjoyed most of the writing, some of the sentences were too long. And I had to think about this before responding. I thought some people simply don’t enjoy long sentences, although if you were looking for an undulating thought that seemed to flow through several ideas at once, nothing did it in quite the same way as a long sentence. As a matter of fact, for the flow I have in mind, a well-constructed long sentence beats out anything else, because it’s simply not possible to compete with that when you have these flagrant periods capping the flow at every turn. A literary journal that doesn’t like long sentences is like a builder of mansions not wanting to use too many bricks. It didn’t quite add up for me. And I mentioned that in my letter of response. But of course it could be that you (the literary journal in question) did not like the particular way I put those sentences together in my piece, which is a valid sentiment.

The other two remarks, however, made me pause far longer than I find comfortable, because the remarks themselves were troubling. One of them declared, “There are many typos and grammatical errors that could have been eliminated with some simple editing.” In archaic nautical terms, this is what they call firing a shot across the bow.

It manifested in me the type of shock you receive when the water you dove into is a lot colder than you had first surmised when you were calculating your jump and never giving a single thought to the temperature of the water.

Typos? They never mentioned what they were, but I knew for a fact they were not talking to me about them. I don’t send out anything until everything is in its proper place. This letter was personalized to the wrong person.

But their last remark confirmed that they made no mistake, that they had intended to send the letter to me after all. And I knew that because they referred to that word I did have in my letter, which was no typo. It was “shit.” They had a problem with this word. Not because it was a bad word. They had a problem because it was in quotation marks, which is often used for quotations by certain personages in a mass of text. The question they had is who was intended to have said it?

Picture this. There are only two people in the essay. I and a stranger. In the essay, there are other quotations, but throughout the text, none of them were made by me. In fact, every single quotation was made by the stranger, who was in the process of talking my ear off, as they say. He was the type of person who openly resorted to profanity even with strangers he had just met. This stranger rarely let me get in a word during our conversation, and I exhibited this during the course of the essay more than once, notably illustrated by the fact that anything I might have said was never in quotation marks. Can you picture it? Moreover, I showed that he was the type who made confrontational remarks, who thought he knew everything and so had to get the last word in. My point is if you read this essay and really gave it the time and consideration, you would know without any doubt who uttered that word.

I left it open without “he said” because it needed no clarification, but I also enjoyed the slight double take on the part of the reader to end this one well. And that is why even though it was obviously not me that said the word, it could have been — on second thought — me. And that was the part they just couldn’t get, this literary journal that did not resort to a form letter, that put all this effort on responding personally to at least one of the submissions that they declined. I don’t know, but this led me to believe that my essay was never even given a proper reading in the first place, and so it forced my hand: I had to send my own argument to their “fine institution of literary excellence that champions the short sentence and math-like clarity.”

I know what I did. I committed a wrong by responding to them. This kind of thing is just not done. I know I really dropped the ball by taking this personally when they didn’t mean to insult. I know that in archaic nautical terms, I sent them a “broadside” in an effort to pull down all their rigging.

And they were one of the nice literary journals that did not deserve such a thing, because they actually cared enough to give personalized responses, even if they failed to read my submission with enough focus. And I know that if I did manage to pull down their rigging along with their sails what the consequences were going to be. They would resort to taking the course of “unfortunately” and “good luck.” But the crime was committed, and when my guilt sank in, the only thing left for me to say was “shit.”

Leave a comment |

Categories: A Thought, Essay, ReyA'

|

Tags: essay, literature