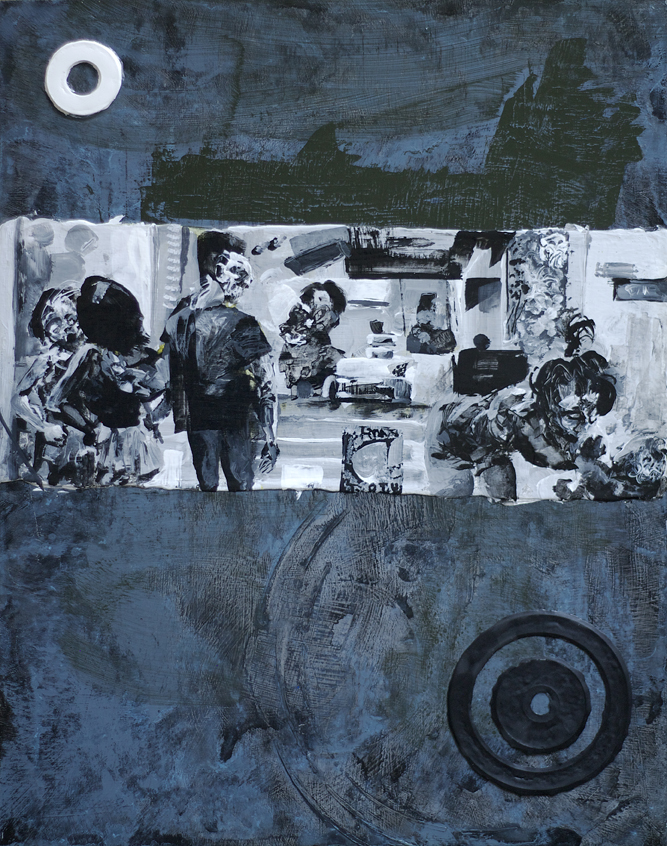

Making Paper out of Paint

by Rey Armenteros

I wanted to get into a paper show. I hadn’t worked on paper in a few years. I called the exhibition space and asked how flexible their definition of paper was. They said, well, what kind of work do you do? I told them I draw and paint on paper I make at home, and then stick that onto a plastic panel. They said that satisfies the definition for works on paper.

I was actually stretching the truth. The “paper” I work on is actually acrylic skin. I make this paper with acrylic grounds and mediums, like modeling paste, gesso, and fluid medium. I apply layers of these substances on silicone sheets. When I’m done with a paint skin, I easily peel it off and adhere it to my painted panel. The work I was going to submit to this show titled, Works on Paper, had no real paper in it. And yet, I wasn’t worried. It wasn’t like they were going to inspect it and then disqualify me.

Ever since this show, I have been looking at my process as a paper-making process. It makes sense. The concept alone propels me into making the many layers of paint to properly make my paper.

It takes over a week to make a small batch of this synthetic paper. I don’t just make these things on silicone sheets; I make them on polyethylene kitchen cutting boards with various textures, and this makes my painting surfaces have the textures of woven papers and laid papers, giving my make-believe paper a world of variability.

The only problem with it is that it is too demanding. It is the same old work, with little variation, year after year. The process of placing spread after spread of paste or gesso is the type of work I don’t find pleasant. It requires no thought but it does require concentration. And this is a bad combination for you if you need some manner of mental interaction in which to sink your teeth into.

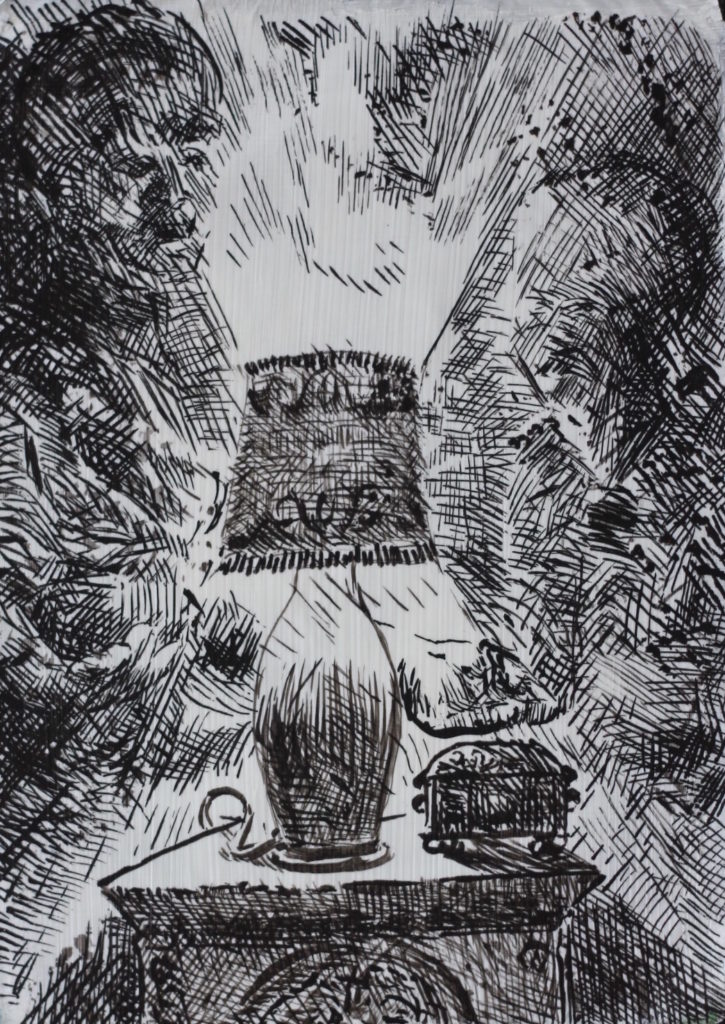

When I am painting, I am completely engaged, working with a concept and executing the steps to get me satisfactory results, making on the spot decisions and changing plans, making the whole drawing and painting process into an elaborate game. The comparison with making plastic paper is accurate. This is the one aspect of my art process that reminds me of the hopelessness brought to life in Albert Camus’ work.

In his novel, The Plague, Camus delivered the same inexorable doom chapter after chapter— you knew exactly where you were going three hundred pages later, and in making skins, you know where you are heading a week and a half later, after hours of work and concentration. Camus’s novel is striking, but I still wonder to this day to what degree I like this one work. It is thoroughly depressing, it puts your life into perspective, it puts on display the most extreme bodily function: that of survival against the inevitable. The characters have nothing to engage with because they are stuck in this city wherein the plague is getting worse, and they can do nothing about the quarantine or their condition. All they can do is wait.

In Japan, I met an old man — he wasn’t exactly an old man; he looked older than he was because of the infirmities that he had to suffer. He had complete white hair. His voice was feeble, and his demeanor whispered the burdens of a convalescing gentleman. But his face was still smooth. We were teaching at this worn out middle school, where the students were in control and the teachers were the last vestige of order and reason against the coming apocalypse.

I was a sort of teacher’s assistant whose only real use in the program was that I was the only one who could speak English in a native accent for the students to try to emulate. The convalescing gentleman was no longer a regular teacher, teaching only some of the time, only when his condition allowed it. He was very surprised by the state of the school.

He would turn suddenly to watch two eighth-graders fighting in the main office, knocking over chairs and slamming into faculty desks, and he’d comment about how bad these students were getting. None of the regular teachers were breaking up the fight — no, a few were actually getting out of the way. That was what it was like in that school, where the teachers were afraid of the students. It took two tall, male teachers a full minute to decide to break up the fight because it was getting serious. They got up and did just that, and my colleague was appalled, and I would have been too if I hadn’t already known the school for what it was. It was that kind of school, the kind I was intimately familiar with growing up in the States, but not the type you would ever associate with Japan.

Student behavior and the teacher reactions to the students were predictable. There was nothing shocking about it once you understood the rules. After a while, we both accepted it.

We would talk about things. We both had ideas we absorbed from books. This recovering teacher was a reader like I was. He confessed that no other book had ever affected him as did The Stranger by Camus. He told me it made him think about things as a young man, and he was never able to reconcile the ideas Camus was presenting with the course of his life. Camus laid out a reality that he did not want to accept but that he could not ignore.

When I read that book a few years later, I thought of my Japanese colleague. It was a story with a simple premise. The notion that someone would gun a stranger down for no other reason than a fickle momentary response was too surreal to take seriously. The inevitability at every stage thereafter was as dependable as water eventually boiling under heat. No surprise ending.

It left me wanting more. I never read it again, but I would recall moments at the beach before the shooting and moments in the jail, and the plain tone that depicted these unlikely and yet unavoidable circumstances digging into a finality and a simplicity that was total.

The rolling of a stone. This is the making of fake paper in an art career. Two plus two equals four. If you say that enough times, you will find just how fascinating this equation actually is. But once your kids understand that there is a connection between this and two times two, and then two to the second power, their minds will begin to find patterns. Patterns can be interesting. They can lead to concepts. Patterns and concepts and many other observations and ideas creep up when I work on images, but they never do when I am making my plastic paper.

In Camus’s version of Sisyphus, Sisyphus rolls the stone up the side of the mountain only to have it roll back down to the bottom. He does this over and over, for eternity. The rolling of the stone exudes the meaninglessness of our actions. It makes me think about what it is I do, and I don’t like to think about that stone.

And this is where my hell is going to be located, with making paper for no good reason. I am going back to an episode of a TV program titled Night Gallery. It was Rod Serling’s short-lived resurgence of Twilight Zone ideas. A hippie ends up in hell, and he’s in a waiting room asking when he was going to be taken in already. The other people waiting alongside him are all manner of annoying people talking to him about every nonsense. Finally, he can’t take it anymore, and he goes to the receptionist window once more and demands to be taken into hell already, and they inform him that the waiting room is his own personal hell, since this was the sort of situation he had always hated when he was alive. Of course, he screams as the other waiting room people harass him, and I can feel his pain because my hell was the one of over and over rolling a meaningless stone, making a dozen sheets of blank, plastic paper, concentrating on this in order to get to the real endeavor, waiting for the day when…