04 April 2021

by Rey Armenteros

The next two books I read of Italo Calvino’s were Mr. Palomar and The Castle of Crossed Destinies. He mentions both of these books in his Six Memos for the Next Millennium, which is not a book of fiction or poetry but one on craft, laid out as lectures he was going to give at a prestigious American university but which alas, never came to be —he died right before taking the trip from Italy to the United States, his lectures remaining unfinished (five memos instead of six, as the title promises).

The actual event of his demise seemed like another juxtaposition incongruously placed alongside with all of the literary concepts he instilled in his books, and if his books each revolved around a conceptual experiment, Calvino’s sudden death even forced a misnomer on the Six Memos. And it was because of what was mentioned in the Six Memos that I was intrigued by Mr. Palomar and The Castle of Crossed Destinies.

In the former book, we have the ill-fated attempt of describing phenomena to the very last detail. Calvino admits in his lectures that this book tries hard to make words shape an object or circumstance as if it were right there in front of us. The question I was asking myself is how many words would you need to completely describe this chair I am sitting on or the window next to me, which opens up to a wide world of infinite detail? Where would one stop?

A more practical question would be how could something like this be interesting to a reader? As I was in the middle of reading Mr. Palomar, I felt that the title character, who is the intellect that is going through these long bouts of description is not just a tool with which to place all these descriptions together. He is also a character. You don’t get anything about him from dialogue or actions that supposedly show character in a novel. Actually, I would never call this book a novel, though I am sure that is how the publishing company sold it to the public. Even though it is not a novel by my definition, it seems to allude to a narrative arc. The book is divided into three parts: Mr. Palomar’s Vacation, Mr. Palomar in the City, and The Silences of Mr. Palomar. In the last one, we seem to go into the interior spaces of the brain, spirit, what-have-you.

As might have been guessed, Mr. Palomar is an inquisitive fellow, always probing phenomena. You go through a set of rules for each chapter that lines up the thoughts in what seems to be a certain order. As I was reading, I harkened back to every philosophy book I had ever read. This commendably does (without succeeding, mind you) what no philosophy book could ever do. In fact, this is how all philosophy books should be written. He blends the facts with that flow of style that I was now starting to recognize as Calvino’s.

(In mentioning his style, I am aware that this was translated from the Italian. But I have always felt that if the translator did the job well, that tone and technique a writer creates will still be there, even if the details of a certain language are disintegrated in the process.)

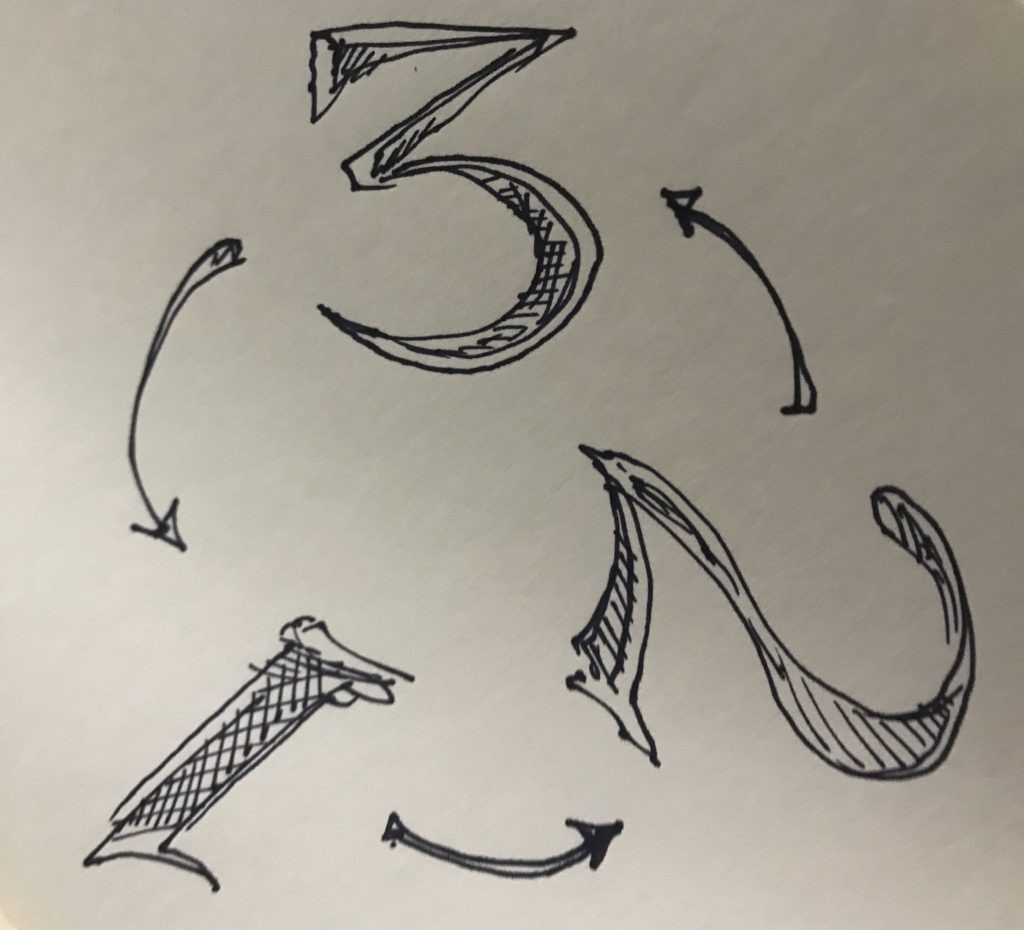

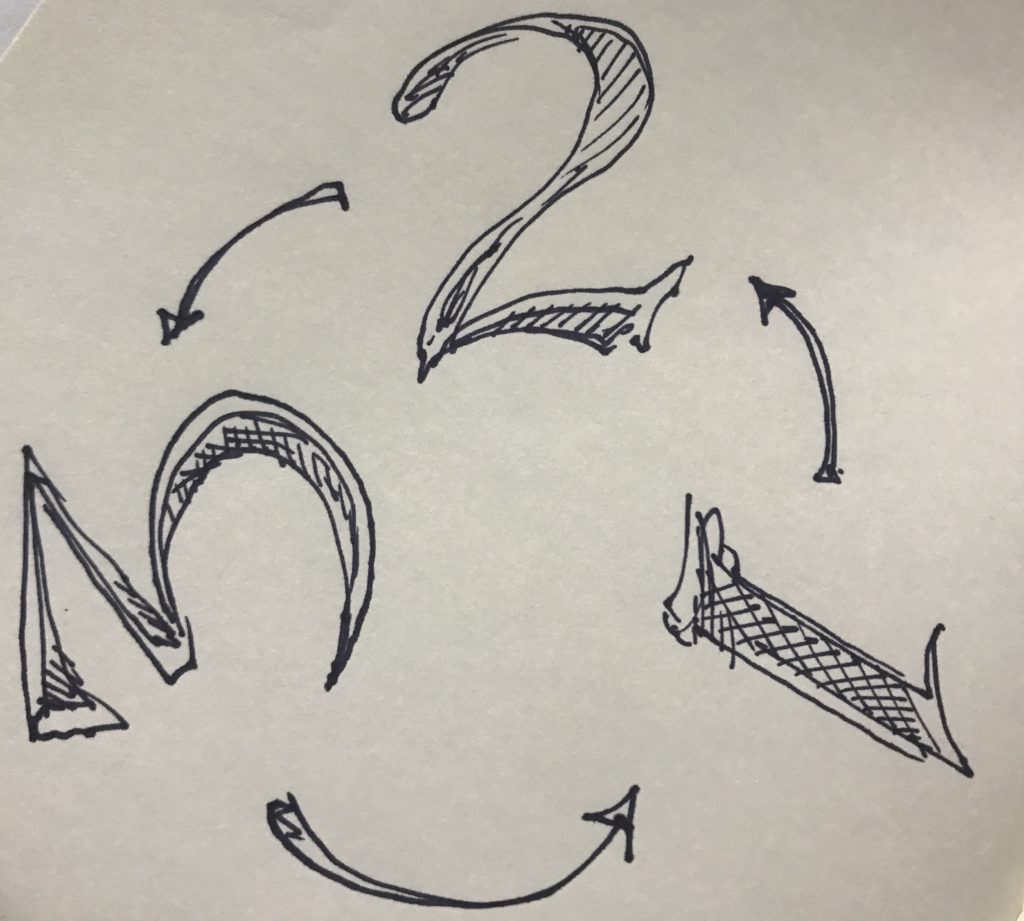

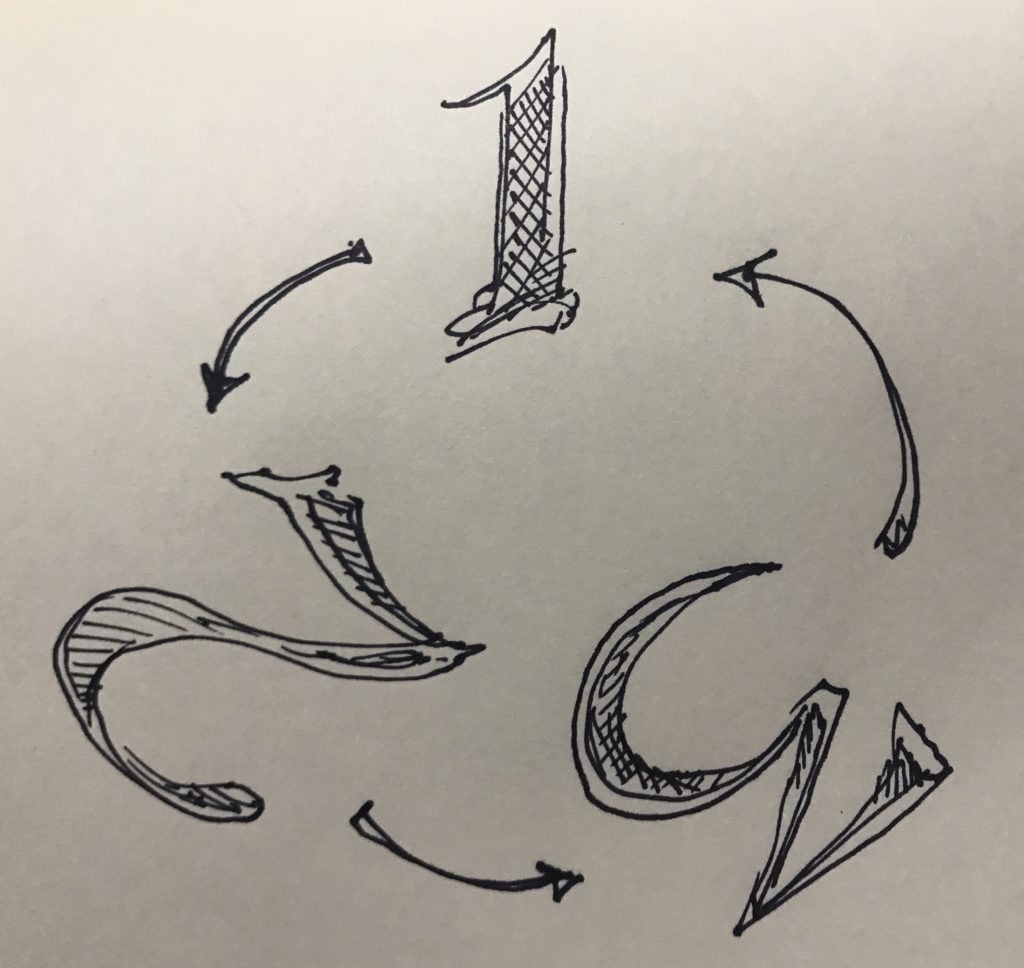

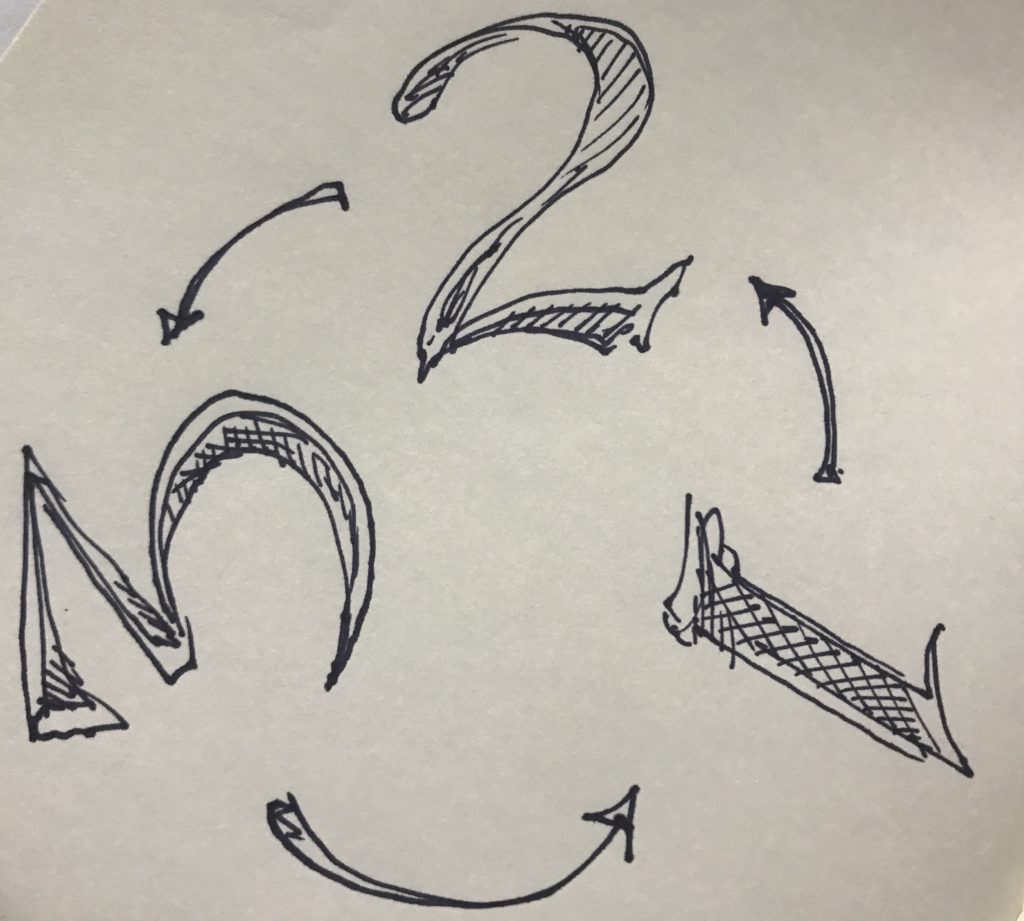

When you read enough of Mr. Palomar, you find that there is a pattern. Each of the three parts has three subsections, and each subsection has three chapters. That makes twenty-seven chapters. The book is symmetrical, and as I was reading along, I was starting to wonder if there were a reason for this. When you get to the end, you find the notes to this book which explain the logic of these numbers. In this book, Calvino was playing a game wherein anything that fell in the first subsection derived from one sphere of human interest, the second fell into another, and the third fell into another. Once again, we had rules set across this book that made me feel that Calvino’s writing was based on premises from which he journeyed to find interesting endings.

This was instantly clear in the second of this group of books, The Castle of Crossed Destinies. Mention of working with the Tarot in his Six Memos was enough to make me seek this book. The narrator finds himself in a castle that is acting like a tavern. Perhaps because of exhaustion, the travelers in this place of rest, sharing food and table space cannot actually utter a word. When anyone in this establishment needs for someone to pass the salt, that person gestures for it. A deck of Tarot cards is produced, and one of the travelers begins to tell a story using the pictures on the cards instead of words. The first card is the Knight of Clubs, and the man on the card has a resemblance to the current tell-taller as if he were saying, “This is me.”

He tells the story by laying out the cards in rows, and the narrator of the actual book is making guesses as to what they really narrate. “It seems that he did this,” or “it is obvious that the woman in the next card is the one he loved.” It is never clear if the guesses are actually the intended story of each silent storyteller.

When one person finishes a story, someone else starts their story by placing cards on the table next to the cards already on the table. So, depending on how the spreads cross each other, the cards used by a previous tale-teller might make an appearance in a later story, and what is interesting is that the meaning of the card might remain the same, and if it does, there are slight changes in it. But the card from this perspective of another narrator might mean something completely different.

The stories themselves are ridiculous fairy tales that involve outlandish situations, including monstrosities and magic. The text is accompanied with illustrations of Tarot cards, and if you pay close attention, you notice that they are presented in fragments of a few cards here and a few cards there, mostly on the margins of the page, and in the same configurations the narrator describes in the story. So, if you trace the placement of the cards in the text, the illustrations follow along. This is an important visual aid, because by the end of the first half of the book, you will find all the cards mentioned in one large tapestry, as it had been mapped out in the story.

The conceptual glue to all of this is that the story of one person crosses in this tapestry into the story of someone else, sometimes contradicting the former narrative. Conclusions are unburied in order for the present narrator to destroy them. And you find that the situation that they find themselves in in this castle-tavern where no one can speak is somehow explained in their disparate stories, and that they all know each other from these circumstances, even though they are acting as if they didn’t.

At the end of the first half, the hostess shuffles the cards, and everything starts anew. Only, when you start the second half of the book, it is as if the travelers stuck in this strange microcosm of hotel and fellow strangers, where no one has the power of speech, are actually in some nightmare or cruel dimension that has sapped everyone of their memory. A new deck of cards is supplied, but curiously, these cards are from a different version of the Tarot (the Marseilles deck), and because of this the digressing details in the cards shape the new stories in different ways.

I was gripped by the ideas behind the narrative being put on a grid of cards that took you somewhere else if you turned right at a card rather than going straight up a column or left in the other direction. But I found that I was reading the words as sounding boards to other ideas that this work manifested in my mind. I was not initially getting the details of the story because after I understood what was happening, I felt they needed too much concentration to understand the relationships. By the second half, I picked up the actual events in the stories with better understanding but had no idea how they tied to the first half, if at all.

I kept going without looking back. And do you know why? Because I was going to buy these two books too, and I was going to have a wonderful opportunity to revisit this insanity now that I had understood the landscape as it was partitioned from the outset by Calvino’s preset laws.

Leave a comment |

Categories: Books, Essay, Poetry

|

Tags: essay, Italo Calvino, literature