Moments with John Paul Leon – Sixth

When enough time had passed, I would send JP a message to ask him if he wanted to talk. If he was up to it, he told me. If he sounded hesitant for some reason, I never pushed the issue.

JP placed my attention on other great artists from the medium. I had seen Zaffino’s work before and remember not liking it on those Punisher graphic novels because it was so over the top, and to me, Punisher was all about unmitigated 1980s violence and vengeance. Since it was pure ridiculousness, I had placed the same value on the art. JP showed me some of Zaffino’s work in black and white, and he changed my mind about him. I soon started seeking out his work in black and white. JP’s prize possession was a Zaffino original he kept not far from his drawing table. He told me Zaffino died young, only fifty. I was worried about JP at the time, because he was going through the treatment, but he was not at all disheartened by it.

He introduced me to the other great Argentine artist, Alberto Breccia. And he introduced me to Sergio Toppi. I had seen a version of one of Breccia’s many styles on the pages of Heavy Metal. It was a quirky silent Dracula story that was painted with expressionistic globs. I quite liked it, but the work JP showed me was different from that. This was Mort Cinder. It was expressionistic too but in a completely different direction, with rough brushstrokes that magically made things look real. I suddenly saw many of our heroes blueprinted on that older artist’s work. Frank Miller never mentioned Breccia, but it was so evident that he had been looking at him when doing Sin City. I was shaking my head, because this was truly phenomenal stuff.

One day, I was getting into Bernie Krigstein. I was on the phone with JP, and I asked him what he thought about him. He described Krigstein’s work as somewhat sterile — maybe the word he used was detached. I could tell he admired Krigstein, but I found it an interesting way to describe his art. It made me reflect on it. I thought JP referred to Krigstein’s inking. Bernie Krigstein was known as the groundbreaker who would cut up pages to reorganize panels and thus receive many smaller panels that invoked a staccato pacing never before seen in comics. He influenced some of the great comics that would come decades after his short career in the field. I thought about his inking, because it had personality but no body to it. His brushwork and his pen work never fused into each other. They collided. It was almost unfriendly, and come to think of it, I should have thought about Klaus Janson’s work in the 1980s when I was looking at Krigstein’s work, because if Janson was not looking at Krigstein, I don’t know who he was looking at.

In one of these conversations, JP told me that he was talking to my stepdad and had given him my number. Just like Alex when he had done the same thing, JP was apologizing for it, because he felt he should have asked me first. And again, I said I would be glad to hear from my old stepdad. I don’t know if it occurred to me to ask JP for his number. If it did, I didn’t make a move. I guess I was following my tacit belief that we had all the time in the world in front of us.

A year or two later, Krigstein was on my mind again, and I was reading his masterpiece, “Master Race” and other stories that used the collage technique that would come to influence so many in the comic book industry, including Frank Miller, once again. I might have read a commentary about how Krigstein never got you too close to the characters to see their reactions.

It may have been a valid assessment for the later work, but that was not always the case. Most of Krigstein’s work was actually quite conventional. It was only when he felt hampered by EC’s rigid methods that he thought about cutting and pasting the panels. And yes, those later works were definitely keeping you at arm’s length. That might have been what JP was referring to all along. We talked soon after, and I recalled our previous conversation about Krigstein and how he had described his work, and I thought I now understood what he meant by it. But when I told him how Krigstein kept us at arm’s length, he said he had never thought about that. Interesting description, he thought, but he meant the inking.

One of the last artists we talked about was Jim Holdaway. I didn’t know JP thought highly of his work, but it made sense. To me, Holdaway was a luminary that no one in the States knew about. Every time I flipped through his work, I was astonished. I loved Modesty Blaise, as if she were real and someone to be infatuated with. And it was Holdaway that made her come to life, not the stories. I had zero interest for where that strip went when he was gone.

Of course JP liked him. It was JP’s connection to that tradition of cartooning, because it had to do with the “naturalistic” school. I won’t call it cinematic, because Milton Caniff was cinematic but not too naturalistic. JP’s work is more about drawing than it is about movies. His well-rehearsed page layouts were about the page and not about the panels becoming ciphers for the screen. Holdaway and Caniff were comic strip cartoonists, by contrast, and they had no choice but to keep it within the tempo of a ubiquitous sameness. I don’t know Holdaway’s thoughts on it, but I know Caniff was trying to make his work into paper movies. Caniff was the one that brought the sensibilities of movies into comics in the first place.

Yes, JP did work in the movie industry, forming the visuals for Superman Returns and Dark Knight, but his comic book work was about comic books, and the connections between the panels — not about transforming his comic book into a poor man’s movie.

When I think about his work in Ex Machina, it surpassed the work of the regular artist, because the regular artist was about cinematic concerns. He was busy amazing the audience with his ability to convert a comic book into a movie with actors and props and backdrops. That was not what comics were about. When JP did his two issues, they were different. My original reaction to JP’s rendition of Ex Machina was how unfamiliar the characters looked under JP’s hand, even though you could readily-recognize them.

But that was the point! They could never look familiar in anybody else’s hands, and a large part of that was because you had to use the same actors/models for that to happen. Years after reading the entire run of Ex Machina, it is only JP’s work that stands out because it runs truer to comic books.

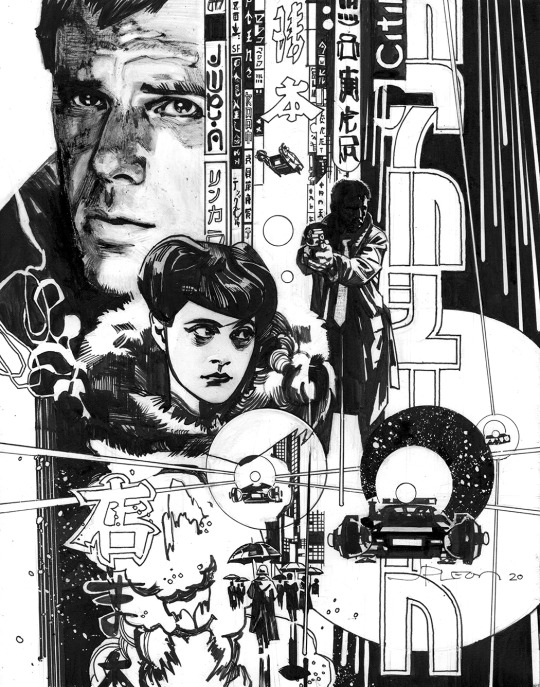

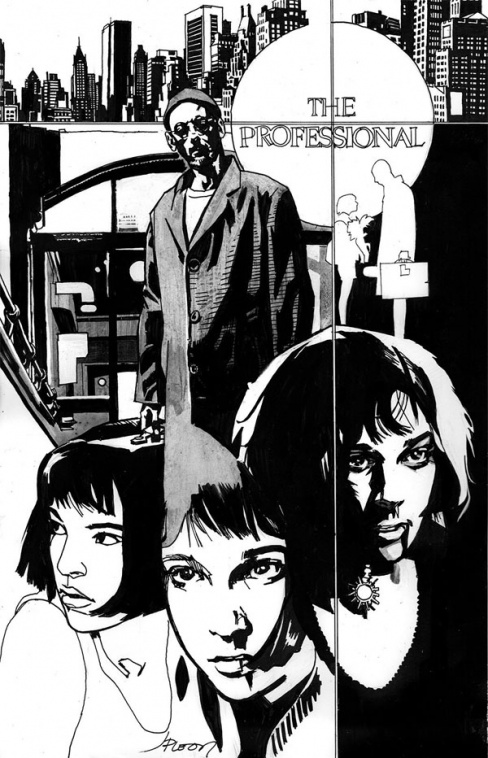

But JP was certainly into movies. He used to tell me about his love for 1970s realism. I think French Connection was one of those movies he held up as a notable work. He didn’t have much to say about current movies, and he lamented the state of the present-day movie posters, because they were nothing more than closeups of actor’s faces. The old movie posters were when you had all these diverse images of characters and situations constructed on the picture plane. You would have a large portrait of one character behind a few full-bodied views of other characters performing some action, as well as places and details in the background that displayed a few instances of what to expect in the movie.

JP’s comic book covers pursue that older tradition of the many-faceted montage in movie posters. There are large views of one or two heads over or behind or under a scene that not just exhibited what was inside; it even offered scenes of what was only suggested in the story.

It’s not like movies did not affect him at all. He was obviously influenced by them, and if you read the Winter Men, you might catch the references to 1970s cinema. But when he did a comic, it was a comic, not a pretend movie.

To JP, I feel it went beyond the comic book, even. To him, it was more about the drawing. It was always about the drawing. I think when he got to the level of work that he had attained, I think the drawing came even before the fun and the entertainment. It became about that. And that is what I guess happens when you are a working professional. JP brought the joy but never at the expense of what he probably held highest — and that was the drawing.